The Edgars! The Thrillers! The Agathas! The Anthonys! The Lefties! The Barrys! Crime fiction awards are fun!

But are all crime fiction awards equally useful? This article will explain why I will be paying most of my attention to the Barry Awards.

From my point of view as a fan and mystery book club leader, the value is in having a list, over a number of years, of “best” books to consider recommending to the group members for a “book of the month.” But, even accepting that there is a lot of subjectivity in saying that any book is the best, are these awards valid indicators for best books of the year in this genre?

In the beginning, there were only the Edgar® Awards (1946). Now there are at least nine entities/organizations that provide book awards exclusively in the crime fiction genre – and that is only in the United States; world-wide, there are many more. Each organization decides on categories of books, some broad (for example, “Best Mystery Novel”) others slightly narrowed (for example, “Best Historical Mystery”), and the decision to have any particular category can change from year to year.

The most enduring category of books, and the first one for books used by the Mystery Writers of America, is “Best First Mystery Novel.” The reason for this prevalent narrow category is stated as “previously unpublished authors bring vital fresh blood to the genre.” So another purpose of the awards is certainly to encourage new writers and fresh thinking.

The U.S. award-giving organizations fall loosely into three categories as follows:

Award Process A: Professional Writer Organizations.

1) The Mystery Writers of America (MWA) that provide the “Edgar® Awards.”

The MWA is essentially a professional organization for published writers. Anyone can join, but only “active members” (published authors) can vote, hold office, and serve on Edgar committees which alone determine the annual Awards. Members volunteer to serve and to judge their peers. For many years, the MWA and the Edgars represented all crime fiction genres from cozy to traditional to thriller; indeed it still does. The Awards are given at a special banquet each year.

2) International Thriller Writers (ITW) provides the “Thriller Awards.”

The ITW began handing out awards in 2007. Like the MWA, you must be an ITW member to participate in the process, or even to have your book selected. (Maybe another purpose of the awards is for some of these organizations to increase their membership and dues). Presumably, the MWA did not give enough opportunity for showcasing the ever popular thriller or suspense oriented crime fiction. That led to the formation of the ITW in 2004, an “honorary society of authors, both fiction and nonfiction, who write books broadly classified as ‘thrillers.’ This would include (but isn’t limited to) such subjects as murder mystery, detective, suspense, horror, supernatural, action, espionage, true crime, war, adventure, and myriad similar subject areas.” The first annual ThrillerFest was in 2006.

CRITIQUE: The specific selection process used by the award committees of these two organizations is somewhat opaque. I can find no list of criteria or other guidance in determining what makes a good book, never mind how the committee(s) go about determining the best book.

Admittedly, the job of choosing books for the “best debut author” category can be especially hard. What if there are no worthy new mystery authors in a given year? Perhaps it would be best to omit that category for a year if that be the case. As an example, the book chosen in the very first year of the Edgar Awards as “Best First [mystery] Novel by an American Author” published in the previous year (1945) was Watchful at Night by Julius Fast.

I was thinking I should get a copy and read it, since it was awarded in the year of my birth. Then again, it is hard to find a reasonably priced copy of the book. It cannot be found in the Commonwealth [Massachusetts library] database either. I notice that 4 people on GoodReads rated it as mediocre and “dated.” Ironically, it was Fast’s first and last mystery book, although he wrote at least a dozen other books in various fiction and non-fiction genres. There is no indication that he contributed to the genre at all.

Then again, unless you are a silent film buff, you may not ever have heard of the first Oscar winner, in 1929, either!

Further, it is not surprising that there is often criticism about both the books that are shortlisted for Edgar prizes as well as those that are selected to win. Larry Gandle, longtime reviewer and critic of the Edgar awards, wrote this regarding the 2021 Edgar shortlist for “Best Book”:

Every year the announcement of the Edgar shortlist is met with some bewilderment for some of the titles included, and most definitely for titles that are excluded. Included are some titles otherwise unknown and excluded are some of the most widely discussed titles of the year. This past year [for 2021 books], George [Easter] and I scoured the internet looking for Crime Fiction Best of the Year lists. … The clear favorite — above any others [on fifty of the “Best of the Year Lists”] — was BLACKTOP WASTELAND by S.A. Cosby. It is not on the [Edgar] list. THE SEARCHER by Tana French was second and is also missing. The fact that these and others were excluded from the list perhaps makes the shortlist somewhat suspect.

— Deadly Pleasures Magazine, Issue 91, Spring 2021, page 19.

I agree! It appears to me that they have, over the years, chosen shining examples of mystery fiction and at other times awarded poorly conceived work.

Award Process B: Convention-Sponsored Award Voting

There are several self-perpetuating, non-profit crime fiction conventions that give out annual “best book” awards based on the votes of those who have registered to attend the events. In all of the cases below, those who have registered for the event are invited to submit ideas for books to be shortlisted. The top books mentioned are placed on the shortlist for each category. Then, prior to the convention, all registered attendees are given the ballot with the shortlists and a deadline for returning the ballot – typically at the convention itself.

3) Bouchercon, The World Mystery Convention gives out the “Anthony Awards.”

This organization convenes its annual convention in honor of Anthony Boucher, the distinguished mystery fiction critic, editor and author. The convention and awards tradition began in 1986, and it selects a different North American region/city each year in which to hold its convention.

4) Malice Domestic selects best books for its various “Agatha® Awards.”

This group held its first convention with awards in 1988, and focuses its activities and awards on “the TRADITIONAL MYSTERY, best typified by the works of AGATHA CHRISTIE. The genre is loosely defined as mysteries that contain no explicit sex, excessive gore, or gratuitous violence, and would not be classified as ‘hard-boiled.'” I wonder if a motive for creating this group was the feeling that the MWA overlooked popular “cozy” authors (in the same way that thriller writers felt led to create ThrillerFest in 2005). This conference has chosen to meet annually in a Maryland city near Washington DC.

5) Left Coast Crime hands out their “Lefty Awards.”

Left (meaning west) Coast Crime was established in 1991 because several fans enjoyed Malice Domestic but didn’t want to go across the country each year. But, as in all of these conventions, the volunteer founders expended huge amounts of hours to get it up and going. There is a sense of humor in all they do (I think it is the only Awards program to include the “Best Humorous Mystery Novel” category; In fact for the first six years, it was the only category.) This conference is held in different cities in the North American “West.”

CRITIQUE: But how reliable are these convention-based award results in identifying the best books?

Let’s first consider the nomination process. I think if there is a large conference with major participation, it should work well, but since nominations are based on what attendees have read, well-known authors with an established reader base and publisher-support will have an edge when it comes to number of nominations that a book gets. Plus, all of the awards are focused on what was published in the preceding year. Many are not yet in libraries. Many convention attendees like myself do not have the awareness or wherewithal to purchase recently published hardback books. All of these concerns are larger when the Convention is early in the year, requiring nominations to be done by March or before. So, I am not sure how much of the nominating process is indirectly impacted by the big publishers and/or best-selling authors. Participation by attendees is voluntary of course, but the more that participate the better.

Now consider the second part, wherein convention attendees vote for the finalist in each category. None of the conventions give guidance to the attendees on this. I think that is a mistake. To me it is logical for voters to read all the nominated books in a category if they are to decide which is best? So these questions arise:

• How many attendees read all the books in each category in which they have chosen to vote?

• How many compromise by reading at least two or three books on the list, and then choose one of the three as the best?

• How many attendees vote for the one book in the group that they read, the one by their favorite author, and might even vote for the book without reading it because they love that author so much?

• How many would like to participate honestly (by reading all the books – usually five or six in a category), but simply do not have enough time to do so because the participation deadlines are overly tight?

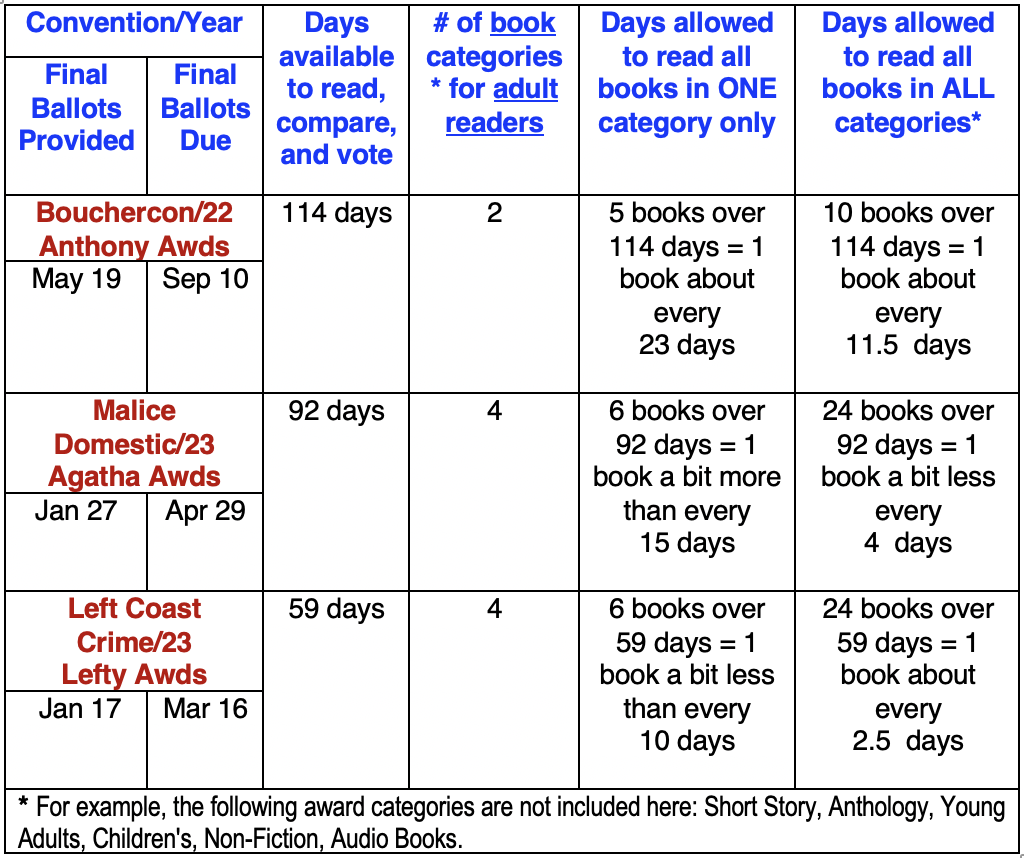

Here are examples and ramifications of moderate and “tight” deadlines:

Clearly having 114 available days to read a pile of books is a lot better than 59 days! Still, my head spins with questions:

• Many of the mystery superfans that work on these conventions and guide the process for their respective award programs read between 40-140 crime fiction books a year. They have likely already read many of the nominated books during the year previous to the conference. Do these leaders assume that most attendees will not need to read many of the nominated books since they have already been read? If so, I think that is unfortunate. In addition to the monthly book chosen for our mystery book club (which is only rarely a book published during the immediately preceding year), I might read one or two more books a month for an annual average of 35 books. It is unlikely that I will have inadvertently read more than one or two books on any of the nominated lists. I am pretty sure that quite a few other attendees are like myself. To vote honestly on the final ballot, we will have a lot of reading to do in a short time following the release of the shortlist. Something I would really enjoy doing, if time permitted.

• Using the data below from the Left Coast Crime Conference, an extreme to be sure, does anyone vote in all four categories, having honestly read all 24 books to actually compare and choose their best in each category?

• If only 40 attendees (out of 500) read all the books in a given category, and vote accordingly, is that a sufficient sample to make the award a meaningful measure of “the best”?

In summary, unless attendees have time to read the books on which they are voting, unless they are encouraged to only vote in categories where they have read all of the 5-7 books, then the result of the voting will be more a factor favored authors. Accordingly, the book chosen as the winner cannot be considered a very reliable recommendation for reading it.

Suggestions:

• Have less than 6 books in the nominated group.

• Present the shortlists earlier, allowing more days to read.

• Put in writing: “Reading the books is expected.” Or, “Only vote within categories where you have read each entry.”

• Do not encourage people to vote by saying, “you don’t have to read them all.”

• Instead of voting for one favorite, use ranked order voting.

Award Process C: Other Variations for Selecting a Prize Winner

There are several in this group but I am only going to discuss one, the one which has the best chance for producing winners that can be relied upon as a solid recommendations for crime fiction fans generally. I certainly will not ignore the results of some of the other award programs, but I take the results of the Barry Awards more seriously.

6) Deadly Pleasures magazine recognizes the best with their “Barry Awards.”

The Barry Awards process is a combination of two ingredients. First, a shortlist is produced for each of 3 categories of books using a slightly messy but thorough integration of both the magazine’s own contributing reviewers and scores of external reviewers. This process has four stages that are described in detail in the Deadly Pleasures magazine; so it is very transparent.

Then, the three shortlists are presented to subscribers of Deadly Pleasures for voting. The awards are presented during a ceremony at the Bouchercon convention. Here is how the number of days for voting compares with the Convention-based awards charted above.

CRITIQUE: As I already stated, I feel this process is the one more likely to generate winners that will be reliable as recommended books for fellow crime fiction fans. One of the FOUR stages in creating the list of nominees includes compiling lists of “top 10” mystery or thriller books and counting how many times a book is mentioned among the lists. Deadly Pleasures identified 85 lists published by others this year! That is broad input! These 85 lists range from those appearing in national newspapers (like the Wall Street Journal), and those appearing on pages of numerous mystery fan-reviewer blogs. I like that. That represents a lot of sifting in many stream beds to find the gold.

I also like the greater number of days for voting which makes reading the books for at least one or two of the three categories very doable. Doable and fun.

Parting Thoughts

In terms of voting this year, I will be reading through the Barry Award shortlists for “Best Mystery or Crime Novel” and “Best Debut Mystery/Crime Novel.” I will vote in one or both if I complete reading the books. BTW, reading 100 pages and ditching it because you do not like the book and don’t want to continue reading it does count as completing a book. It would have to be really bad for me to do that, and I don’t anticipate books rising to the top to give me that reaction. 🙂

For quick reference to all the award programs, historical results, and a weblink to more information, go to http://www.stopyourekillingme.com/Awards/index.html

For more information about the Conventions mentioned in this article, go to https://www.mysterybookfan.com/mystery-book-conferences/

As fun and appealing as the idea of a “Best Mystery” book may be, mystery reading groups, like our own group here in Manchester include members who prefer and those who eschew cozy mysteries, spy or political thrillers, medical thrillers, psychological mystery/thrillers, private eye stories, and so on. With that in mind, it can also be useful to consider the members’ tastes and sprinkle the calendar carefully according to taste, by…

- finding a best humorous mystery from the Lefty Awards

- finding a best cozy or traditional mystery from the Agatha Awards

- finding a best private investigator mystery from the Shamus Awards

- finding a best thriller from the Thriller Awards and the specific category in the Barry Awards

- finding a best historical mystery from the specific categories in the Lefty Awards and Agatha Awards,